#Java Batik

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Batik Fabled Cloth of Java

Inger McCabe Elliott

collabration Paramita Abdurachman, Susan Blum, Iwan Tirta, photo by Brian Clarke

Periplus Editions, Hong Kong 2004, 240 pages, 23x30,5cm, paperback, ISBN978-0-7946-0668-8

euro 40,00

email if you want to buy [email protected]

Batik: Fabled Cloth of Java is a sumptuous, classic book, richly illustrated with color plates of the finest antique and contemporary batik from thirty museums and private collections around the world. It includes historical photographs, etchings, engravings, maps and photographs of modern Java.

10/03/24

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

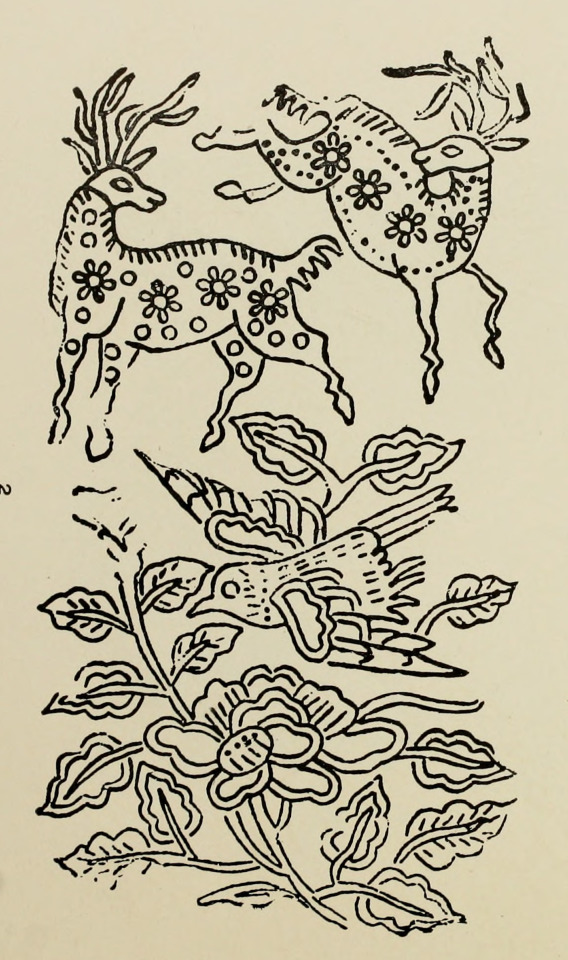

Spotted deer. Javanese batik designs from metal stamps. 1924.

Internet Archive

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

The Javanese in Sri Lanka represent a small yet historically and culturally significant ethnic minority group whose roots trace back to the island of Java in modern-day Indonesia. While today their numbers are relatively modest, their legacy reveals a complex tapestry of colonial-era migration, religious and cultural transformation, and assimilation within the broader Moor and Malay communities of Sri Lanka. The Javanese presence in Sri Lanka is deeply interwoven with the dynamics of European colonialism in Southeast Asia and the Indian Ocean world, particularly during the Dutch and British periods. Despite the limited size of the community, their influence has been disproportionately rich in terms of religious practice, cultural retention, and social history.

The migration of Javanese individuals to Sri Lanka began primarily during the period of Dutch colonial rule in the Indian Ocean, particularly in the 17th and 18th centuries. The Dutch East India Company (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie, or VOC), which had consolidated control over both Ceylon (modern-day Sri Lanka) and the Dutch East Indies (modern-day Indonesia), often transferred populations across its colonial holdings for administrative, military, and punitive purposes.

A significant portion of the Javanese population in Sri Lanka arrived not as voluntary migrants but as political exiles, slaves, or convicts. Many were members of the Javanese aristocracy or resistance leaders who opposed Dutch rule. These individuals, deemed a threat to colonial control, were exiled from Java to Dutch colonial outposts, including Sri Lanka. One of the most notable cases is that of Prince Susuhunan Pakubuwono II of Surakarta’s entourage and other noble figures who were exiled for their roles in uprisings or suspected subversion. Alongside these elites were soldiers and laborers, including artisans and religious figures, who were brought to Ceylon to serve in various capacities under Dutch command.

This forced migration created a diaspora community that was geographically dislocated but culturally vibrant, maintaining ties to Javanese customs, language, and especially Islam. The migration of Javanese to Sri Lanka also included people from other parts of the Indonesian archipelago, such as Madura and Sumatra, further enriching the ethnic mosaic that would come to be associated with the Sri Lankan Malays, among whom the Javanese would be culturally subsumed over time.

Over the centuries, the Javanese in Sri Lanka were gradually absorbed into the broader "Malay" community—a category that includes peoples from the Malay Archipelago brought to Sri Lanka during the Dutch and British colonial periods. This umbrella term has obscured the distinct ethnic identities of Javanese, Bugis, and other Southeast Asian groups, but it has also provided a collective identity that allowed these migrants and their descendants to maintain a degree of cultural cohesion.

The Malays in Sri Lanka, including those of Javanese descent, primarily settled in the coastal and urban areas of the Western and Southern provinces, including Colombo, Kandy, Hambantota, and Galle. These settlements were often established near colonial administrative centers or military installations where Malays served as soldiers in colonial militias, police, and other service positions.

Javanese linguistic influence in Sri Lanka has largely receded, with Malay and Sinhala being more commonly spoken among descendants. However, vestiges of Javanese vocabulary, particularly in ritual contexts and family heritage, persist in some Malay households. The use of Javanese honorifics, titles, and naming conventions was once common among elite Javanese families in Sri Lanka, especially those descended from nobility.

Religion has played a central role in preserving Javanese identity in Sri Lanka. The majority of Javanese migrants were Muslim, and their Islamic practices aligned with the broader Malay community, which facilitated communal integration. However, the form of Islam practiced by the Javanese often retained elements of Javanese religious culture, including Sufi mysticism and syncretic rituals rooted in pre-Islamic traditions.

Some of the earliest mosques established by the Malays and Javanese in Sri Lanka became centers of religious learning and cultural preservation. These institutions often taught Arabic, Malay, and basic Javanese texts, especially during the 18th and 19th centuries. The Mawlid celebrations, communal prayer sessions, and recitations often featured uniquely Javanese Islamic chants and devotional literature. In particular, Javanese-style Qur'anic recitation and religious poetry—such as syair—were prominent in religious festivities.

Traditional Javanese dress, culinary practices, and ritual customs survived in modified forms. For example, dishes such as "nasi goreng," "sambal," and "satay" made their way into the broader Sri Lankan Malay culinary tradition, although often with localized ingredients. Celebrations such as weddings, coming-of-age ceremonies, and religious festivals still bear traces of Javanese customs, such as batik garments, gamelan-inspired musical rhythms, and traditional Javanese court etiquette.

During the colonial period, Javanese-descended individuals, like other Malays, held positions in the colonial military and police forces. They were considered reliable by the Dutch and later the British due to their perceived loyalty and martial skill. These roles afforded some degree of upward mobility, though they remained socially marginalized compared to the majority Sinhalese and Tamil populations.

In post-independence Sri Lanka, the Javanese community—largely merged into the Malays—has maintained a modest but active presence in political, social, and religious spheres. Malay organizations such as the Sri Lanka Malay Confederation and local mosques have played crucial roles in advocating for minority rights and preserving cultural heritage. While the Javanese identity is often subsumed under the Malay label, some families continue to preserve genealogies and oral histories that trace their roots specifically to Java.

Javanese Sri Lankans have occasionally served as bridges between Sri Lanka and Indonesia, particularly in diplomatic and cultural exchanges. The Indonesian Embassy in Colombo has supported cultural preservation efforts and highlighted the shared heritage between the two countries, sometimes hosting events featuring Javanese dance, music, and cuisine to reconnect diasporic communities with their ancestral culture.

As with many small diaspora communities, assimilation, intermarriage, and modern urbanization have contributed to the erosion of a distinct Javanese identity in Sri Lanka. The younger generation is often more integrated into Sinhala or Tamil linguistic and cultural spheres, and many no longer speak Malay, let alone Javanese. Yet, there is a growing recognition among scholars and cultural activists of the need to document and preserve this unique historical legacy.

Academic interest in the Javanese of Sri Lanka has increased in recent decades, particularly within the fields of Southeast Asian studies, Islamic history, and migration studies. Researchers have focused on archival materials from the VOC, Dutch legal records, family trees, oral traditions, and religious texts to reconstruct the history of Javanese migration and settlement. These studies reveal a community that, while numerically small, made a meaningful contribution to Sri Lanka’s multicultural heritage.

Efforts to preserve the legacy of Javanese Sri Lankans have also included community-based oral history projects, digital archiving of old photographs and documents, and collaborative projects between Sri Lankan Malays and Indonesian cultural organizations. The story of the Javanese in Sri Lanka is increasingly seen not just as a local phenomenon, but as part of a broader narrative of Indian Ocean migrations and the transnational histories of Islam and colonialism.

The Javanese in Sri Lanka represent a microcosm of the broader diasporic experiences shaped by colonialism, forced migration, and cultural resilience. Though many have been absorbed into the larger Malay community, the distinct historical and cultural contributions of Javanese Sri Lankans remain an important part of the island’s diverse social fabric. Their legacy offers insight into the complexities of identity, heritage, and survival in the context of displacement and assimilation. As modern efforts to preserve this heritage grow, the story of the Javanese in Sri Lanka continues to enrich understandings of both Sri Lankan and Southeast Asian history.

#javanese#sri lanka#sri lankan history#javanese diaspora#indian ocean history#colonial history#ethnic studies#cultural heritage#malay sri lanka#islamic history#javanese culture#indonesian diaspora#southeast asia#sri lankan muslims#batik art#javanese traditions#forgotten histories#minority voices#sri lankan malays#diaspora culture#javanese aesthetics#historical migration#ethnography#sri lankan culture#indonesian heritage#java to ceylon#postcolonial studies#muslim communities#oral histories#island histories

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Javanese batik weavers from Batavia, modern-day Jakarta, Java, Indonesia

American vintage postcard, mailed in 1934 to Southbury, CT, US

#ephemera#mailed#photography#modern#vintage#briefkaart#batik#indonesia#java#carte postale#postcard#photo#jakarta#southbury#sepia#ansichtskarte#weavers#modern-day#postkarte#javanese#1934#postkaart#postal#batavia#american#tarjeta#historic

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Java, Indonesia (2) (3) (4) by Caspar Tromp

Via Flickr:

(1) Traditional house, Yogyakarta (3) Traditional Javanese masks. (4) A bustling bazaar full of traditional batik clothing.

#traditional house#around the neighborhood#masks#people#market#market stalls#bazaar#indonesia#java#yogyakarta#batik#bunting

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Our new product is a concrete kawung batik patterned design. Can add to your collection! In Javanese culture, the geometrically arranged kawung motif is interpreted as a symbol of human life. The hope is that humans will not forget their origins. Apart from that, the kawung batik motif is also known as a symbol of strength and justice.

0 notes

Text

i haven't posted anything here omg kinda nervous... but here's zutara in traditional javanese wedding attire 🙇🏻♀️ commissioned this from my friend she's amazing 😖❗️

some facts about the attire! ☺️😙

The headwear these babies are wearing are called Blangkon and Cunduk Mentul, Blangkon is a traditional headwear worn by men usually in Central Javanese and Yogyakarta (especially the one Zuko is wearing!) The word Blangkon itself is said to came from the word 'blanco' referring to the blank cloth used to make the headwear, tho there are soo many theories about the origin of both the headwear and the name itself cause sadly there aren't many records about it :(

The headwear is also used to represent wisdom and class because back then, these were used to differentiate the nobilities from the commoners (wr don't really do that anymore dw). The Javanese people believe that your hair, head, and face are the most important and treasured parts of your body, so these Blangkon are used to protect those parts. We also believe that Blangkon represent self-control, since Javanese men tend to keep their hair long back then and keep them loose when they're in a state of 'conflict' such as battles or war, representing uncontrollable flow of emotions so keeping their hair up and covered is seen as an act of self control.

As for the Cunduk Mentul, these pretty headpieces are typically worn by brides on their wedding day! They represent 'the sun that shines over the universe' and also... well, it depends on the number of the pieces they use, usually it's 1, 3, 5, 7, or 9, each representing a different value. 1 is used as a symbol of God's singularity, usually worn by muslim brides, 3 is for the Trimurti or the Trinity of Hindu Gods that deeply rooted in Javanese values, 5 is for the five pillars of Islam, 7 symbolizes 'help' or 'aid'- the Javanese believe that 7 is a lucky number since 7 is 'pitu' in Javanese, so, yeah, 'pitu' for 'pitulungan' or help and aid in Javanese language. 9 represent the Nine Saints/Wali Sanga, 9 saints that have a major impact on the growth of Islam in the island of Java.

Their clothing respectively are called Beskap and Kebaya 🤩 Beskap is more of a modern version of Javenese traditional clothing, for it was adopted from the modern suits worn by the Deutsch during the colonization era. The word Beskap came from the word 'beschaafd', meaning civilized (oh!)

Kebaya, on the other hand, has no specific area origin cause each region has their own styles and versions! The one Katara is wearing is a Central Java Kebaya tho, famous for the velvety fabric and dark colors along with the gold motifs. The history of 'modern' Kebaya itself started in the 15th century when Dutch first settled in Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia!) The clothing had taken inspirations from different cultures (like Chinese and Indian) along the way since Indonesia was (kinda still is!) One of the centers of trade routes for both Hindia and Pacific Oceans.

Damn I'm getting tired of writing this, but next 😭 is Kain Jarik! A piece of fabric with Batik motives wrapped around the legs :))) these babies have RANGE, like they could be used daily, for traditional dance attire, sacred rituals, weddings, even used in funerals 😀 they're usually 2 to 3 meters in length and more variations in width, easy to customize! They also usually have dark colors like dark brown and light brown motives, but i asked my friend to draw them with red and blue and gold motives cause why not 😝

Anyways I think i went a little overboard cause my fingers are hurting from typing this lol.

#zutara#zutarian#zuko x katara#katara#zuko#atla fanart#atla#zutara fanart#fanart#atla zutara#traditional clothing#javanese#idk how to tag this#is this okay?#anyway#commission#art commisions

302 notes

·

View notes

Text

thinking today about how much I love literally all fiber arts. I am hopeless at almost every other kind of art, but as soon as there is thread, yarn, or string I can figure it out fairly quickly.

I learned how to knit when i was eight, started sewing at nine, my dad taught me rock climbing knots around that age, I figured out from a book how to make friendship bracelets, I've made my own drop spindle to make yarn with, and more recently I've picked up visible mending. I've learned embroidery through fixing my overalls, and this year I've learned how to darn and how to do sashiko (which I did for the first time today). After years of being unable to crochet I finally figured it out last night and made seven granny squares in just a few hours.

I want to learn every fiber art that I can. I want to quilt, I want to use a spinning wheel, I want to weave, I want to learn tatting, I want to learn how to weave a basket, I want to learn them all. If I could travel through time and meet anyone in the Bible, high on my list are the craftsmen who made the Tabernacle.

I want to travel the world and learn the fiber arts of every culture, from the gorgeous Mayan weaving in Guatemala, to the stunning batik of Java, to Kente in Ghana. I want to sit at the feet of experienced men and women and watch them do their craft expertly and learn from them.

Of every art form I've seen, it's fiber arts that tug most at my heartstrings.

#Fiber arts#fibre arts#knitting#Sewing#Mending#visible mending#sashiko#Darning#friendship bracelets#Spinning#drop spindle#embroidery#crochet#quilting#Tatting#weaving#basket weaving#Mayan fabric#Kente#Batik

972 notes

·

View notes

Text

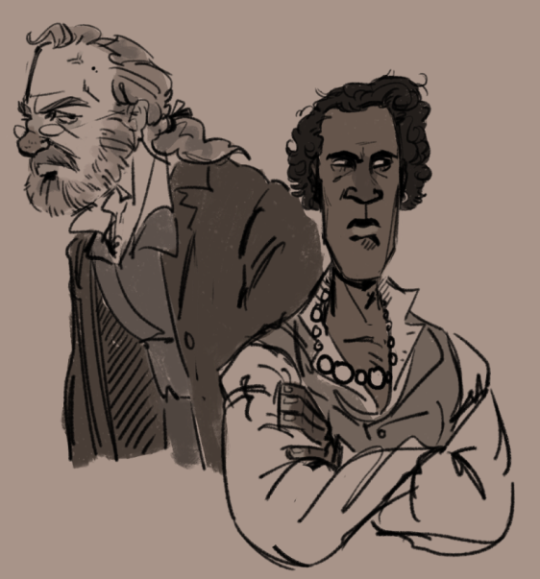

Enjolras (& Grantaire)

While not really a presence in what i'm usually writing about, I still wanted to design them. Enjolras certainly is more relevant than Grantaire when I'm writing about Marius, though. Sorry !

With a blond/..er, frosted tips? Version. Cause I know blondjolras is like canon and all but I'm not sure which I prefer.

Grantaire's design is still very much in the early stages, and whether it will ever leave them still remains to be seen . I didn't draw him in colour, but he is indeed ginger and taller than enjolras, thanks Kyle Adams! (With credit to Tom Hext)

So! Design details!

My Enjolras is Javanese. Representing this (to the best of my very british ability) is his sarong (the garment around his waist). While not Javanese in essence, Enjolras is not currently living in Java/Indonesia to be able to receive that direct cultural influence. Some batik (the name of the textile pattern) would have had european influence. This can be seen in the design I have created in the branches, which I tried to base on the tree brances seen on the symbol of the French Revolution.

Also on the batik is a fleur-de-lis, and alongside the french flag stipes on the trim, connects the indonesian to the french. Admittedly the addition of the fleur-de-lis doesnt really make much sense considering it wasn't particularly used much after the Revolution, so that might end up getting changed.

The necklace he wears is also javanese in origin - admittedly I should really have looked at a reference as they are NOT made from beads, so that would be an amendment for later, but he wears that also to represent his heritage. It also somewhat symbolises his more fortunate background.

His earring is simply for flair, however since they weren't particularly common, I guess it's him straying from the status quo.

Same goes for the bleached hair - purely to stand out. But I'm not sure if that's a permanent addition to his design yet.

In my first design I had him wearing trousers and shoes, but I've changed it to a pair of boots, as they are more militaristic in nature and practical.

As for grantaire... not much to say. He looks older than his days, a bit bloated, certainly his swollen alcoholic's nose too. Hair's grown long as he's stopped caring about getting it cut and styled at the barber, but hates how cropped hair makes his head feel cold. I'd say that's the situation with his beard too - can't be arsed getting it shaved.

Anyway.... next post will probably be about the old men, don't worry. Just needed to get this out of my system.

Any requests or questions about them or the other amis are totally welcomed - but i can't guarantee i'll have a decent answer past these 2 or courfeyrac. SORRY

85 notes

·

View notes

Text

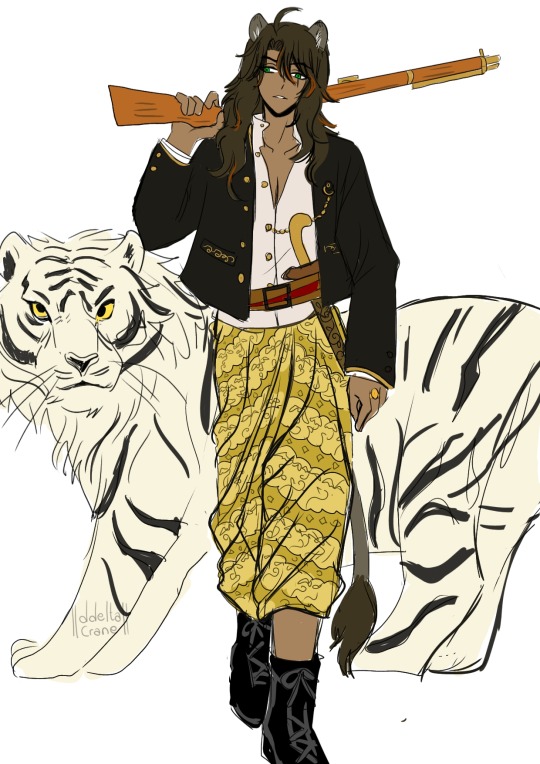

Hehe. Its beskap (similar to like javanese tribe ones, back then it was used by royals) and batik too.

Also add white tiger because my tribe believe white tiger spirit guards our nature and people.

(I am from Sunda tribe, West Java btw)

Twitter

Commission info

#drawing#illustration#twst#twisted wonderland#leona kingscholar#indonesia#sunda attire#beskap#traditional attire#twst fan art#leona twst#twst leona

816 notes

·

View notes

Text

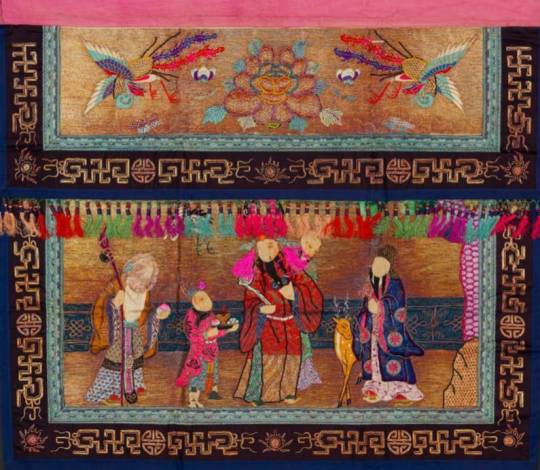

Peranakan altar cloth (tok wi in Baba Malay)

Decorating the fronts of altars during important ceremonies, these cloths reflect the strong ritual elements of Chinese Peranakan life in Southeast Asia. Families traditionally used embroidered cloths made in southern China, but in the early 20th century, some in Indonesia began using cloths of local batik.

Batik is resist-dyed cloth, originally made in India and then taken up in Java by many ethnic groups. Made on the north coast of Java, these batik altar cloths show traditional Chinese symbols as well as designs from Europe and Southeast Asia. They are an example of how art evolves according to local traditions.

Sources, including more examples and background if you want to explore further! — roots.sg // NHB

#I made this post just so I could pin these lmao#More people need to see them#Not only is it so gorgeous to look at#It's also just one perfect example of art & history & geography & religion & nature & mythology culminating into something beautiful#and its all handmade! each one is unique! they're not just purely aesthetic. each has a story with the historical and mythical references

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Batik Printing Blocks (Tjaps) Unidentified makers (Java)

intricate copper stamps used to create patterns for wax resist printing

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

Batik Sarong

MAKER: Elza Van Zuylen

DATE: C. 1900

PLACE MADE: Java, Java, Indonesia, Southeast Asia, Asia

MEDIUM: Cotton

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yogyakarta: Java’s Cultural Gem and a Family Adventure Awaits

Yogyakarta, or Jogja as the locals warmly call it, is a city where the rhythm of ancient rituals blends seamlessly with the hum of modern life. Nestled in the heart of Java, Yogyakarta is a treasure trove of cultural wonders, where majestic temples, royal palaces, and timeless arts beckon explorers of all ages. For families looking to embark on a journey that transcends time and place, this city offers an enchanting playground filled with history, adventure, and the warmth of Javanese hospitality.

Timeless Temples: Unraveling the Mysteries of Prambanan and Borobudur

A trip to Yogyakarta wouldn’t be complete without visiting its iconic temples—two of Southeast Asia’s most awe-inspiring UNESCO World Heritage Sites:

Prambanan: Rising against the horizon, Prambanan’s towering spires carve out a story of 10th-century Hindu majesty. Its intricate stone reliefs depict ancient legends, drawing families into a realm of gods, warriors, and mystical creatures. Arriving at dawn, as the temple silhouettes against the first light, is a moment of quiet wonder that families will cherish long after they leave.

Borobudur: The world’s largest Buddhist monument, Borobudur is a massive stone mandala that invites contemplation and exploration. Climbing its steep, stone steps at sunrise reveals panoramic views of mist-laden valleys—an unforgettable experience for curious young adventurers and their parents alike. Walking through the temple’s nine platforms, families can trace their hands over centuries-old carvings that tell tales of enlightenment.

Kraton and Taman Sari: Walking in the Sultan’s Footsteps

In the heart of Yogyakarta lies the Kraton, the living palace of the Sultan. More than just an architectural marvel, the Kraton is a cultural hub where traditional Javanese music and dance fill the air. Families can wander through its expansive courtyards, where ceremonial guards stand in stately silence, and exhibits showcase the regal artifacts of a bygone era. The Kraton provides a window into the city’s soul—a place where past and present harmoniously coexist.

Nearby, the Taman Sari Water Castle offers another layer of royal intrigue. This labyrinthine garden complex, once a retreat for the Sultan, features pools, tunnels, and pavilions that spark the imagination of young explorers. With a local guide, families can hear stories passed down through generations, adding depth to their visit and a sense of the magic that still lingers in these ancient stones.

Art and Craft: Jogja’s Heartbeat of Creativity

Yogyakarta pulses with an artistic spirit, a city where creativity flourishes in every corner. As the birthplace of wayang kulit (shadow puppetry) and batik, Yogyakarta invites families to immerse themselves in Java’s rich artistic heritage. In the city’s vibrant workshops, artisans demonstrate the delicate art of batik-making, allowing children and parents alike to try their hand at this age-old craft. Each brushstroke and drop of wax is a lesson in patience and tradition, transforming plain fabric into colorful masterpieces.

For those seeking an immersive experience, staying near Malioboro Street offers a front-row seat to Jogja’s bustling arts scene. Galleries, street performers, and markets create a lively atmosphere that’s perfect for families looking to soak in the city’s creative energy.

Adventures Beyond the City: Yogyakarta’s Natural Wonders

Beyond its cultural treasures, Yogyakarta opens up to landscapes that call for adventure:

Java’s Southern Shores: The beaches of Parangtritis and Indrayanti are ideal for a family day out, where children can run barefoot through the sand and parents can relax by the waves. At Siung Beach, cliffs rise above the coastline, offering rock climbing opportunities for thrill-seekers ready to conquer the heights with a view of the sea.

The Depths of Goa Jomblang: For older children and parents with a taste for the extraordinary, descending into the vertical cave of Goa Jomblang is a heart-pounding experience. Families can rappel into a hidden world, where shafts of sunlight pierce the cave’s roof and illuminate an underground forest—a moment of surreal beauty that feels like stepping into a lost realm.

A Taste of Jogja: Culinary Delights for the Family

Yogyakarta’s culinary scene is a feast for the senses, with flavors that capture the essence of Javanese cuisine:

Gudeg: This sweet, savory dish made from young jackfruit is a Jogja staple, served alongside rice, chicken, and boiled eggs. Malioboro Street is lined with family-friendly eateries where parents and kids can share this traditional dish, savoring the rich, coconut-infused flavors that are unique to the region.

Bakpia: These small, flaky pastries filled with sweet mung bean or chocolate make for the perfect snack between adventures. They’re also a popular souvenir, allowing families to take a piece of Jogja’s sweetness home.

Jamu: For parents interested in local wellness traditions, Jamu—Java’s traditional herbal tonic—is a must-try. Some family-friendly hotels even offer Jamu-making classes, giving visitors a hands-on experience in crafting these ancient remedies.

Staying in Jogja: Family-Friendly Retreats

Choosing the right accommodation can transform a family vacation into a seamless adventure. Yogyakarta offers a range of kid-friendly hotels that cater to every type of traveler:

1. The Jayakarta Hotel & Spa Yogyakarta

Set near the airport, this family-friendly oasis offers a children’s pool, playground, and lush gardens for kids to explore. Parents can unwind at the spa, making it the perfect base for families looking to combine comfort with convenience.

2. Royal Ambarrukmo Yogyakarta

A heritage hotel infused with Javanese elegance, the Royal Ambarrukmo provides a cultural experience for the entire family. With its traditional tea ceremonies and an on-site kids’ club, families can balance cultural immersion with playful activities.

3. Eastparc Hotel Yogyakarta

For families looking for fun-filled stays, Eastparc Hotel delivers. Boasting a water park, playgrounds, and a mini cinema, it’s a paradise for children. Parents can explore the botanical trails or enjoy a massage at the hotel’s spa—ensuring every member of the family is entertained and pampered.

Exploring Yogyakarta: A City on Wheels

Getting around Yogyakarta is an adventure in itself. Families can hop into a becak (pedicab) or take a ride on an andong (horse-drawn carriage), offering a leisurely way to soak in the city’s historic charm. For those seeking a more active exploration, bicycles are available for rent, allowing families to venture into the countryside, discover hidden temples, and cycle through traditional villages at their own pace.

Yogyakarta: A Timeless Journey for Families

Yogyakarta isn’t just a destination; it’s a journey through the heart of Java, where the stories of past and present unfold before your eyes. Whether you’re tracing ancient paths at Borobudur, tasting the flavors of Gudeg, or creating batik masterpieces with your children, every moment in Jogja is a chance to connect, learn, and explore.

Families who visit will find themselves swept up in the city’s timeless charm and warm hospitality, leaving with memories that linger long after the journey ends. Yogyakarta—where every step tells a story, and every turn invites discovery—awaits to share its magic.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Day 4 Fashion/Pattern : Batik

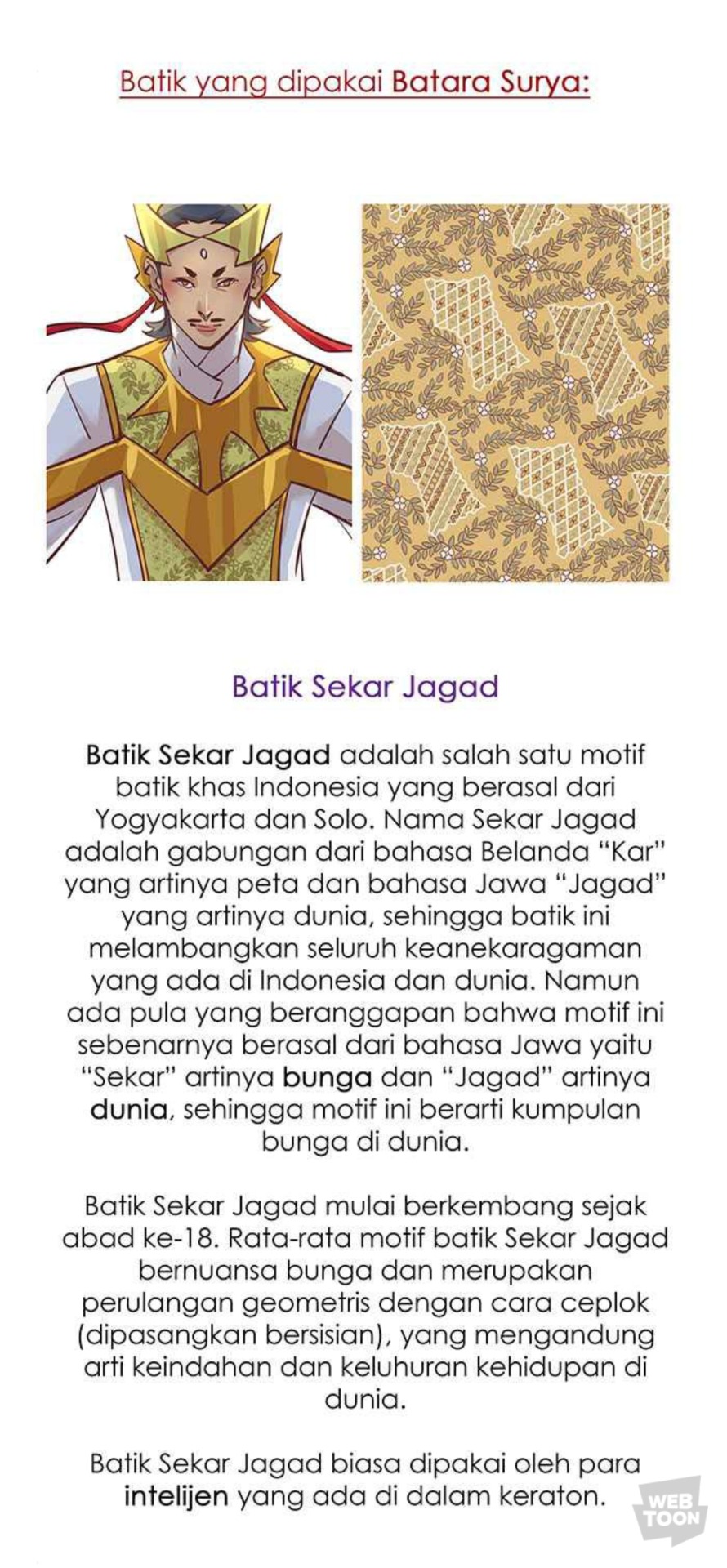

taken from another webtoon which is this :

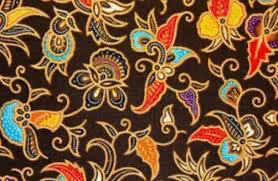

Batik is an Indonesian technique of wax-resist dyeing applied to the whole cloth. This technique originated from the island of Java, Indonesia. Batik is made either by drawing dots and lines of the resist with a spouted tool called a canting, or by printing the resist with a copper stamp called a cap.

Also here the collection of the batik after this, from my OC Princess Wreksa from Batik kingdom! Batik kingdom is island-based kingdom that colorful in every aspects

14 notes

·

View notes